This article argues that the distinctions we make in peacebuilding masks a messier, highly interdependent reality that we need to honestly engage with. We argue for a more holistic, systems view, and present three case studies of explicitly systemic peacebuilding strategies from Myanmar and Thailand. Reflection on these case studies offers insights for systemic theories of change, including engaging multiple parts of the system in parallel, rewiring relationships within the system, balancing adaptation and control, and building trust with donors to balance risk.

—–

During much of 2009, the development economists Jeffrey Sachs, Dambisa Moyo, and William Easterly carried out an acrimonious debate on The Huffington Post concerning the relative merits of international aid in addressing global poverty. This feud, which was sparked by the release of Moyo’s book “Dead Aid“, was a heavyweight encounter between competing grand ideas in international development.

Easterly framed this as a contest between Planners, who see poverty alleviation as a technical challenge that can be overcome by top down, expertly-designed, and centrally-controlled programs, versus Searchers, who foster smaller, independent processes that are more indigenous to the context, learn from trial and error, and survive or perish based upon more consequential assessments of their performance.

The polar positions of this debate, no doubt hardened by the degree of ego involved, left little space for a more prosaic view. There should not be a binary question of whether we need planning or searching approaches. A more realistic question would be how these strategies (and the stakeholders that implement them) should work together to make the entire system of poverty alleviation more effective overall, depending upon the nuances of where and in relation to what we are working.

An analogous debate in peacebuilding concerns the relative merits of top-down versus bottom up approaches. This debate stratifies peacebuilding stakeholders from international actors and processes on top (or outside) through to various actors within host countries, including for example elites, civil societies and communities. Lederach’s seminal work on building peace, the emerging inclusivity norm, or the important but somewhat jaded local turn offer alternative entry points into this debate. Once again, this language has been useful to advance peacebuilding discourse and practice, but masks a reality that is infinitely messier, interconnected, and emergent.

THE MERIT OF A SYSTEMS VIEW

Sweet is the lore which Nature brings;

Our meddling intellect

Mis-shapes the beauteous forms of things:—

We murder to dissect.

– William Wordsworth

‘Top down’ and ‘bottom up’ concepts are one of many categorisations that we use in order to describe and differentiate amongst a diverse system of actors, processes, roles, and relationships in peacebuilding. We often see peacebuilding processes as horizontal efforts to repair relationships between groups, or bridge across divides in conflict-affected societies. We separate between HQ and the field, policy and practice, and subdivide our work in countless thematic lines. We distinguish between the roles and relative merits of insider and outsider peacebuilders, and peg our policies to arguably meaningless temporal distinctions between conflict prevention, peace enforcement, post-conflict peacebuilding, etc.

The benefit of these categories is that they render a indescribably complex and dynamic reality comprehensible, provide a common language for communication, and provide a framework upon which to hang our policies and rationalise resources. The problem of distinguishing and separating elements of the peacebuilding system in this way, however, is that it narrows our focus, and masks the reality that outcomes of peacebuilding are determined not by any one element of the system, but through all of their complex interactions over time. This narrowing of vision becomes especially pronounced when we become attached to the relative merits of some stakeholders or processes, a la Easterly and Sachs, or when our geography, identities, policies, institutions, values, or resources confine us to limited pockets of this world.

Systems approaches to peacebuilding, in contrast, recognise that conflict results from the dynamic interaction of many actors and processes over time. They challenge us to understand these causal patterns and appreciate their non-linear qualities, which render some interventions useless, create unintended consequences, or – ideally – offer potential for impacts much greater than our inputs. Systems approaches to peacebuilding offer these impacts when we work indirectly to reconfigure the causal relationships that give rise to problems, rather than than narrowly focusing on problems. We can only optimise impact if we recognise that our understanding of the context will always be inaccurate, and that our theories of change are forever hypothetical, and subject to adaption as we learn, and as the context changes.

So what do these strategies look like?

WORKING IN SYSTEMS

At some level all this talk of systemic causality is quite obvious. We all realise that we’re part of a much broader and interconnected set of actors and processes, and that we must work together if we’re going to be effective. Various commentators speak of the need to work more effectively across boundaries in peacebuilding. But understanding that we’re part of a system is not the same as working systemically, explicitly, with concepts and tools adapted from systems thinking and complexity theory. People and organisations wishing to begin the systems practice journey can access a variety of resources for understanding systems concepts or applying systems mapping to build better strategy.

But wait, this is not peacebuilding!

Some of you will look at these examples and assert that the activities that they describe are not peacebuilding. And you might be right, to an extent. These cases are not easily recognisable as efforts to transform violent inter-group conflict, or even to address obvious root causes of violence. Practitioners at a field level will note, however, that definitions of what constitute peacebuilding can get quite blurry in conflict-affected areas, especially when one asks ordinary people what peace means to them. But if you still find that these examples aren’t closely linked enough to peacebuilding – fair enough, and please share with us some better examples. In the meantime, we hope that these cases are still relevant conceptually.

What has sometimes been missing amidst the recent hype about systems approaches, however, are strategies and examples of actually working in systems. In contrast to analysis or planning, working in systems refers to the actual “doing”; the implementation of strategies for peacebuilding based on explicitly systemic theories of change.

The case studies presented here, in different ways, posit that 1) because peacebuilding challenges are borne of multiple causes, the probability of successful peacebuilding will increase when multiple actors and multiple issues are engaged simultaneously, 2) the likelihood of succeeding where previous efforts have failed when increase when stakeholders are connected that are not like-situated or like-minded, 3) change should be unlocked from within, not imposed from the outside, and 4) that it’s difficult to know a priori what the most effective peacebuilding activities will be in a given context. We’ll reflect more on these towards the end.

SYSTEMIC ACTION RESEARCH TO TACKLE DRUG ABUSE IN MYANMAR

In May 2015 seventeen people gathered in a large meeting hall of a hotel in a small, dusty town on the China-Myanmar border. Their topic was opium and amphetamine abuse amongst local communities. That a group was discussing drug abuse in Myanmar was not unusual. Myanmar is the world’s second largest producer of opium, and home to a drug epidemic that for decades has been largely invisible from outside of the country. What was unique however was the composition of the group.

Sat in a circle facing each other that day was a diverse mix of policemen, prison guards, public health officials, drug dealers, internally displaced people, pastors, opium farmers, current drug users, ex-drug users, and representatives of community based organisations. Some of these people regularly interacted. Drug dealers, for instance, might regularly meet and transact with drug users, or opium farmers. Prison guards and policemen regularly interact, and encounter drug dealers and drug users when they apprehended. But never before had such a diverse group all met together. The facilitator that day was challenged to effectively manage the tensions that arose. The aim of their meeting: to understand the causes of drug problems holistically and consider more effective means by which they could be addressed.

The facilitators had bought this diverse group together because they had recognised that in order to understand drug abuse, they needed to know how drug cultivation, use and abuse, commercial exploitation, conflict and insecurity, psychosocial trauma, policy and institutional responses, and a whole host of other factors combined in ways that allowed catastrophic drug problems to persist despite their best efforts. A useful way to arrive at this understanding, they surmised, was to bring together a group of people that together ‘touched all parts of the system’. They had also realised, moreover, that centrally planned approaches to tackle community drug abuse were failing, and that by connecting and diversifying their relationships, they could access new networks, find novel opportunities for constructive action, and seed potential change processes in a wider range of spaces.

The facilitators were following a process of Systemic Action Research, which was implemented in northern Myanmar from 2013-2016. Systemic Action Researchers collect narratives of lived experience from community members, and analyse these using systems mapping, so as to develop a more holistic understanding of what causes problems in their communities. They then form action research groups – like the one that emerged from the above conversation – to develop, implement and evaluate strategies. The ensuing process of working via local networks is highly adaptive to learning through implementation and changing contextual requirements.

Six months after the meeting described above, these researchers had implemented a range of activities to address community drug abuse. The initiatives are notable for the range of stakeholders involved and diversity of theories of change (e.g. attitudinal, institutional).

Pastors were recruited to preach non-discrimination against former drug users during their sermons, to limit the social marginalisation that problematises recovery and compels relapse. Prohibitions against the sale of drugs in camps for internally displaced people were introduced. Lobbying efforts resulted in changes to public policy to favour rehabilitation rather than punitive strategies, which were unintentionally increasing access to drugs for incarcerated people. Drawing competitions, theater productions, and radio shows were produced in order to build awareness around the risks of drug use, particularly among youth. And for the first time, drug awareness curricula were introduced in high schools.

These strategies utilised network resources such as schools, IDP camps, and radio stations to maximise the reach of messages, co-opted influential people such as pastors to maximise attitudinal change, and sought sustainability of positive changes through adjustments to curricula and law.

CONFRONTING BONDED LABOUR IN THE THAI SEAFOOD INDUSTRY

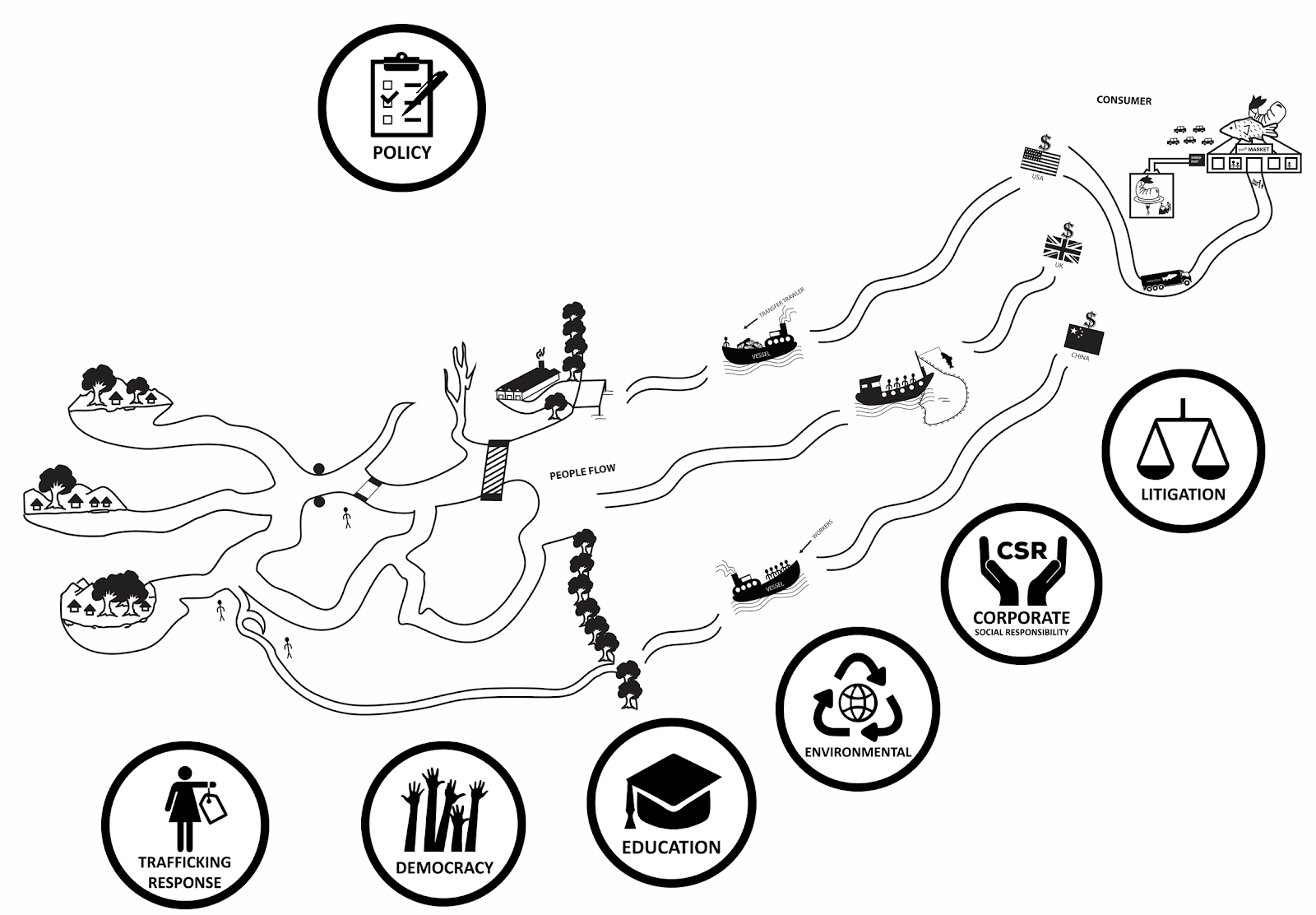

Across the border in Thailand, the Freedom Fund began using its grantmaking resources in 2015 to address the complex problem of bonded labour in the Thai fishing industry. Bonded labour – a form of modern slavery – takes place in Thailand when economic migrants from neighbouring countries incur debt to labour brokers who promise them lucrative jobs in construction, manufacturing, and agriculture in exchange for transport and job-placement fees. This debt is often transferred to owners of seafood processing factories or fishing boats, resulting in bonded labour.

Some of these migrants end up on Thailand’s estimated 50,000 unregistered “ghost ships”, which sort their catch onboard and transfer it to other ships, so a boat may not dock or allow labourers ashore for months or years. These labourers’ efforts contribute to a $2.5 billion annual fisheries export market to the US and Europe alone. Customers who buy these products rarely appreciate that their consumption inadvertently supports practices of bonded labour, which is hidden in a range of corporate supply chains, including pet food and fish sauce.

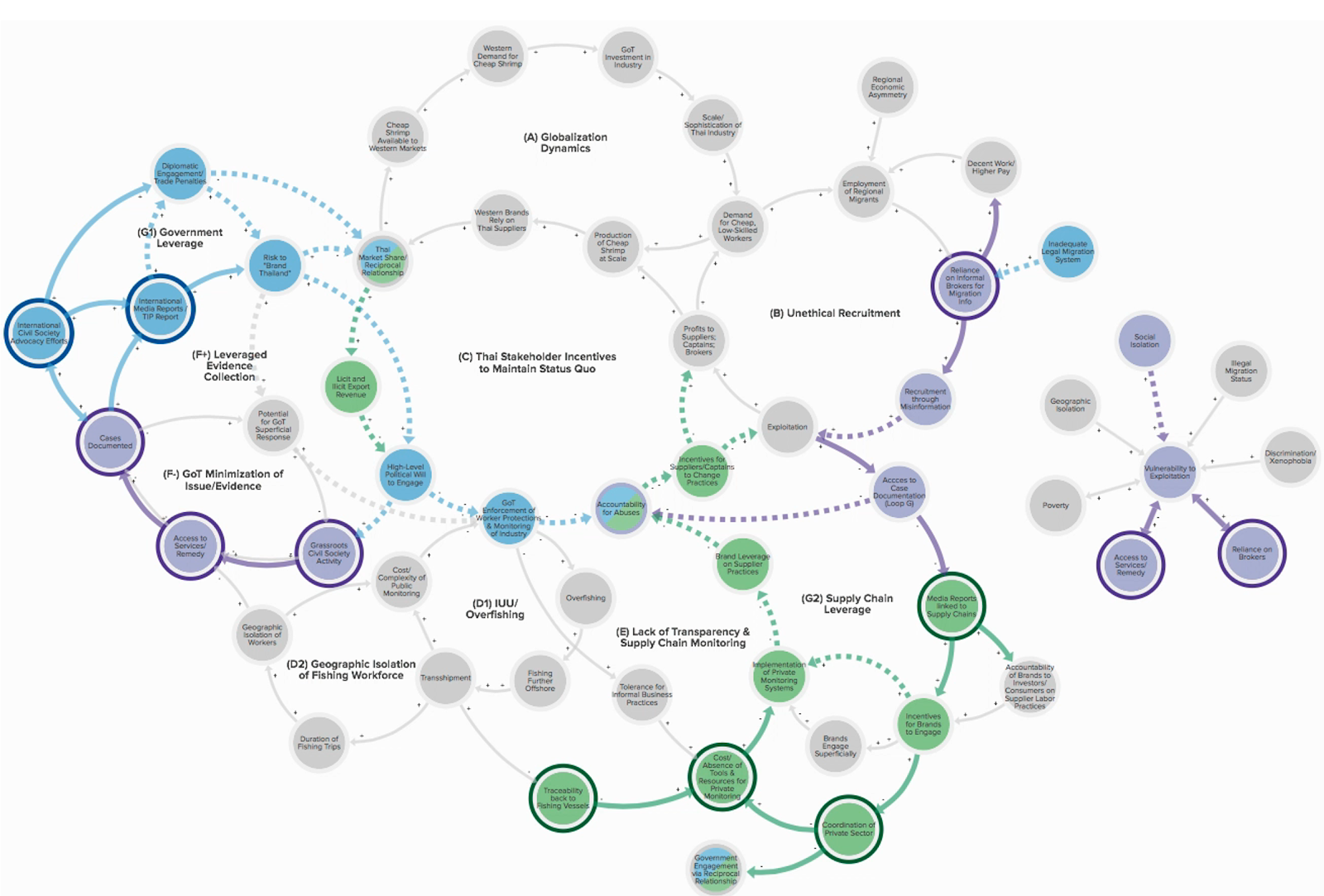

For the Freedom Fund, addressing such a complex problem required engaging multiple parts of the system in a coordinated approach. Like the example of community drug abuse in Myanmar, practitioners used systems mapping to understand the way that local and global economic, policy and migration patterns were giving rise to the emergent problem of bonded labour.

This analysis provided the rationale for a $5 million initiative that seeks to create change via a network of partners that with unique intersections with the fisheries industry globally to locally. Civil society coalitions are supported to inform and influence executive bodies at national, European and International Level. Leading global news agencies have been funded to conduct investigative reporting that exposes bonded labour practices. Technical advice has been provided to multiple global industry-led efforts to achieve transparency and oversight of corporate supply chains. Thai and regional governments have been supported to improve the regulatory framework, undertake effective inspections at sea, and aggressively prosecute traffickers and abusive business owners. Technical assistance is provided to the Thai Department of fisheries to promote compliance with vessel monitoring system requirements and use of these systems in satellite surveillance. Corrupt local officials that flout the law have been exposed by civil society partners on Facebook Live. Grassroots partners are funded to provide shelter, legal aid, and rights protections for migrant workers. Local health partners are resourced to provide better mental health services for survivors.

The Freedom Fund’s systems practice recognises that the problem of bonded labour arises due to interaction of various causes across geographies, from push factors associated of poverty in emigre countries, to consumer pull factors for cheap products in destination markets. Any one intervention in this causal web by itself is unlikely to reliably eliminate bonded labour, as long as the ultimate impact of any initiative is contingent upon or might be undermined by other factors. New legislation is worth little, for instance, if state institutions don’t have the resources or integrity to uphold it. As long as enabling factors and incentives towards bonded labour remain that overpower sources of inhibition, interventions that address a narrow set of causes – such as push factors for economic migration or pull factors for affected products – risk simply pushing these factors into different markets.

PYOE PIN: TRANSFORMING THE INLAND FISHERIES SECTOR IN MYANMAR

Credit to Duncan Green @ Oxfam (and his excellent from Poverty to Power blog) and the good folks at Pyoe Pin for their Myanmar fisheries example.

The Pyoe Pin Programme tries to promote social and political change in Myanmar by bringing together coalitions of individuals and interest groups to address particular issues of social, political, environmental and economic concern. These coalitions often establish new relationships and ways of working between sometimes adversarial groups, like non-state actors, professional and academic organisations, government, parliamentarians, businesses, and civil societies. Efforts are made to include in these coalitions decision makers or other people with authority and influence, making use of personal contacts, family networks and trusted insiders. Coalitions can also foster links between individuals who are regionally dispersed. Pyoe Pin supports these coalitions through iterative, adaptive process of collaborative problem solving and trust-building related to each issue, which results in collective efforts to formalise social, political and environmental improvements, often in the form of new laws or publicly responsive policy processes. Most of Pyoe Pin’s spending is earmarked for activities by local partners. Pyoe Pin’s approach relies on inspirational leaders who can create alliances, build trust, and adapt to sensitive and changing dynamics.

An example from Pyoe Pin’s work in Myanmar’s fisheries sector demonstrates the approach. In early 2012 Pyoe Pin began working in western Rakhine State, where it helped establish the multi-stakeholder Rakhine Fisheries Partnership (RFP), comprised of members of parliament, civil society, the Department of Fisheries, lawyers, private sector, and fisher communities of different ethnicities. When civil unrest and communal violence swept through Rakhine State in 2012, the international community was expelled, but the RFP continued to engage communities of different faiths who had mutual interest in improved fisheries practices, and conflict risk mitigation for the protection of the state’s economic and social development. In 2013 the RFP began drafting a new fisheries law, which for the first time in Myanmar included public consultation, including with persecuted Muslim communities. The new law ended the tender license system that was contributing to illegal fishing and land conflicts. The success of these reforms, built off the back of unique civil society public coalitions and first-ever consultations between legislators and the general public, led to the initiation of a national multi-stakeholder body which is developing a comprehensive national policy framework across four sub-sectors: offshore, inshore, freshwater and aquaculture.

THEORIES OF CHANGE IN SYSTEMS STRATEGIES

These case studies offer useful reflections to inform the development and deployment of strategies for systems change, which are sometimes called leverage hypotheses in systems practice.

Engage multiple parts of the system. In the Myanmar examples multiple stakeholders were combined into collaborative change processes. Freedom Fund’s work against bonded labour across multiple partners has been less collaborative, but no less systemic, insofar as it has supported multiple complementary actors and processes whose efforts in total have the potential for systemic change. All of the approaches recognised that these complex problems could not be solved by magic bullets, but through affecting multiple causal dynamics in the system that led to an overall change its emergent properties (i.e. by alleviating community drug abuse, or bonded labour). This is sometimes described as seeing patterns, not just problems.

Rewire relationships. Novel change opportunities in the drug abuse and bonded labour examples came through new collaborations and coalescing interests, particularly between actors were not like situated or like minded. In practice this meant innovating collaborations between stakeholders normally separated by ‘horizontal’ divides like ethnicity, geography, insider/outsider status, or organisational or political affiliation, or ‘vertical’ strata such from the general public, through to civil societies and elites. These connections were made possible through the exceptional work of development entrepreneurs who could build trust and harmonise interests between stakeholders, as well as expert facilitation processes that created safe spaces and managed tensions in sometimes fraught group processes. Both Myanmar examples also utilised research processes for shared knowledge creation, which provided a consensual basis for new collaborative actions.

Unlocking rather than imposing solutions. In each of the cases presented, external supporters of these initiatives have played roles as catalysts of change, rather than imposing plans upon local stakeholders. Catalysis comes in the form of financial resources, in the bonded labour example, or by providing resources (financial and research) as well as process facilitation, as in the community drug abuse and Rakhine fisheries cases.

Balance external control with context-driven adaptation. The Sachs and Easterly debate from the beginning of this post contrasted the relative merits of top down central planning methods that pre-determine means and ends, versus bottom up approaches that allow means and ends of peacebuilding to emerge from the interaction of stakeholders in the context. The systems strategies that we’ve seen suggest the value of blending both, though they tend to favour more distributed agency, and relatively adaptive approaches compared to centrally-planned peacebuilding. Both Myanmar cases took the context rather than external plans as a starting point for selecting topics to focus on, but the decisions were not entirely random nor democratic. Political economy analysis and systemic action research provided the rationales for these topics, respectively, and external supporters considered strategic criteria, including the potential for alignment of interests among local stakeholders. And while these approaches had

a high degree of process flexibility, insofar as local stakeholders chose the specific activities to pursue their peacebuilding goals, these emerged from pre-designed processes, such as systemic action research groups, or coalitions. These examples are not purely context-driven nor design-determined, and demonstrate instead the value of a middle way that establishes process backbones which ensure the necessary conditions for context-driven innovation.

Keep your friends close, and your donors closer. Systems strategies can be challenging for donors to support, particularly when these approaches utilise adaptive management. It’s more challenging to demonstrate impact, especially when activities build gradually towards systemic change. Donor confidence can also be tested when partners cannot predict their activities in advance, or seek to change them during the course of implementation. In each of the cases presented here, donors and implementing organisations have had a shared belief in the value of a systems approach and have sought to ensure accountability in adaptive processes by collaborating in programmatic decision-making, and documenting the rationale for changing directions.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

These cases help inform theories of change for more systemic approaches to peacebuilding, which recognise the dynamic and interconnected nature of the societal processes that we must engage with. They also leave a range of questions that deserve further exploration. First up, did the use of systems strategies work better than conventional approaches? The short answer is yes – the Pyoe Pin folks behind the Rakhine fisheries example at least one DFID’s 2014 supreme award – though it’s be interesting to unpack why. Did multiple interventions induce a tipping point? Can positive impacts be linked to transformation of particular causal dynamics?

We’ll be exploring this topic in more depth over the coming months. We’d love to hear your thoughts.